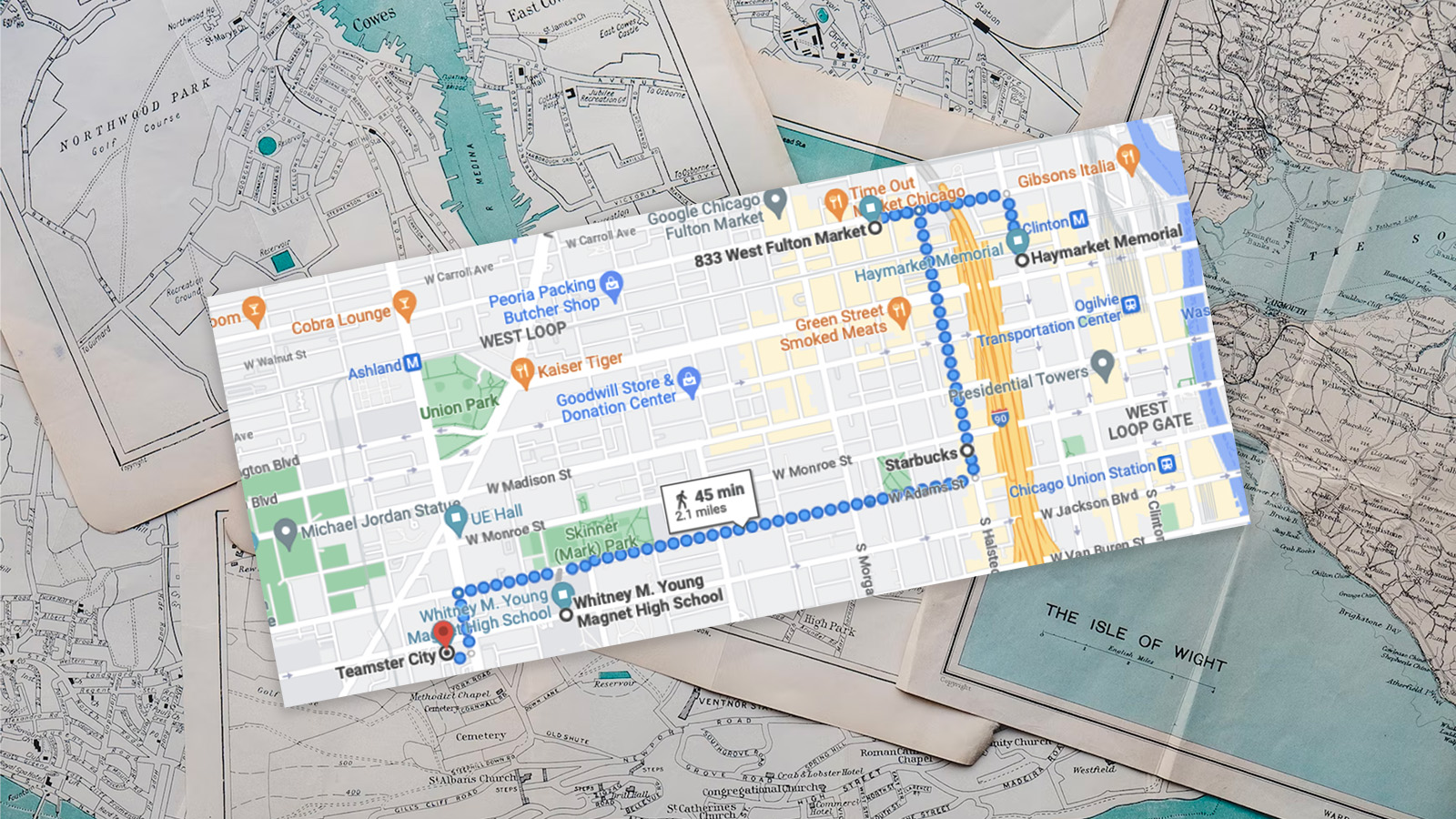

On Saturday, April 22nd, Chicago DSA’s Political Education & Policy committee will host a that will bring together speakers from across the labor movement to highlight important sites in Chicago’s rich labor history. Our path will illuminate the political forces that shaped, and were shaped by, the city of Chicago. It also tells a bigger story, tracing the arc of the labor movement over its 150+ year history in the United States: A history where socialists have been at the forefront, driving the movement forward, inspiring the ire —and often violent retaliation— of the capitalist class by demanding labor’s due.

The fates of the socialist movement and the labor movement are historically intertwined. The first American mass labor movement was born of class struggle in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. Because of the city’s rivers, railroads, position on the Great Lakes, and access to raw materials, Chicago saw dramatic growth. Leveraging their wartime contracts, the capitalists, oligarchs and robber barons consolidated power and deployed world-changing industrial technology at scale, and the city swelled with immigrant labor. German, Irish, British, and Scandinavian working and peasant classes powered Chicago’s booming industry in the 1860s and 70s. Some were steeped in the international socialist movement that had emerged on the European continent. And as the turbulent, brutal inequality of the Gilded Age advanced across a fractured nation, labor became ever more militant in its demands.

Some of the most iconic struggles occurred in Chicago’s meatpacking industry, where the mass production of livestock transformed America’s food system, as well as the conditions of labor for its workers. Socialist muckraker Upton Sinclair brought infamy to the industry with his 1906 novel The Jungle, describing the grim realities of Chicago’s Union Stockyards. The national campaign for the eight-hour workday took shape in the Stockyards, fueling socialist and anarchist agitators, and ultimately producing the bloody events of the Haymarket Affair in 1886.

People-powered movements require the exercise of solidarity; America’s first surging labor movements often broke themselves against the seawalls of exclusionary racism and xenophobia. Karl Marx himself understood that the racialized social hierarchy of America was an impediment to labor becoming organized, let alone amassing and exercising political power. “In the United States of America, every independent workers’ movement was paralyzed as long as slavery disfigured a part of the republic,” he wrote in Volume I of Capital. “However, a new life immediately arose from the death of slavery. The first fruit of the American Civil War was the eight hours agitation, which ran from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from New England to California, with the seven-league boots of a locomotive.”

At the turn of the century, labor organizers grappled with these forces in Chicago. Campaigns in the stockyards were sundered as craft unions refused to admit Black workers, and the bosses hired Black and immigrant workers as strikebreakers. Efforts collapsed as racial antagonism and white supremacist violence roiled Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919. In the 1930s, Black worker-organizers took the lead, laying the foundations for intentional, multi-racial mass organizing drives. The Congress of Industrial Organizations, under the influence of the American Communist Party (CPUSA), successfully organized tens of thousands of Stockyard workers across racial and ethnic lines.

But the 20th century also saw waves of successful Red scares, pinning the blame for social upheaval squarely on the Left, and resulting in the expulsion of CPUSA organizers from their leading roles in organized labor. Mid-century developments in logistics opened the way for the meatpacking industry to decamp from the city to rural areas, bringing in yet another wave of non-unionized immigrant labor. In 1971 the Union Stockyards closed for good, and within a matter of years, deindustrialization began to sweep across the Midwest. America’s overall union density has declined dramatically since then for many reasons, including globalization & offshoring, business unionism & concessionary bargaining, anti-union legislation such as right-to-work, unchecked corporate monopoly power, the dominance of finance capital in the modern economy, and a political class largely untethered to the realities of working-class life.

Today, the vibrant heart of organized labor is in public sector unions. In particular, the Caucus of Rank-and-file Educators that gained control of the Chicago Teachers Union has led the way for educators across the country to wield their power through strategically withholding their essential labor. Through their strikes in 2012 and 2019, CTU flexed their power by bargaining for the common good, including strike demands like social workers and affordable housing for the 17,000+ homeless students in Chicago Public Schools. And in recent years, as runaway inequality leaves more and more people behind, service and logistics sector organizing has surged, driven by the rank-and-file. With victorious reform caucuses making waves in powerful unions like UAW and the Teamsters, labor power is on the rise again.

As Democratic Socialists, we envision socialism as Eugene Debs described it: “merely an extension of the ideal of democracy into the economic field.” The union is the working-class institution that allows working people some measure of control over the places where we spend a third or more of our precious time. We know the world does not function without the workers caring for our children, delivering our packages, preparing our food, and providing our healthcare.

to join us on Saturday, April 22nd at 1 pm to see where the world as we know it was made: in the streets, where the socialist movement and labor movement came together in militant action.